I appreciate that my photographs are very different to what the majority of people would consider makes a good photograph of the Tower of London, for this I make no excuses. In a lecture recently I was asked by a student about my relationship to the audience/viewers of my photographs. My answer was simple – when I’m making a body of images I give the audience no thought what so ever. I added that I thought that as soon as you start thinking about how your photographs will be received you are on the road to making formulaic photographs of no worth.

With this said (and the final prints well under way) I would like to try and explain what i see in a particular image and why I chose it over a seemingly similar photograph. Next week I will also post my inrodution to the final piece, which will explain my collected thoughts on the residency and the photographs I have produced.

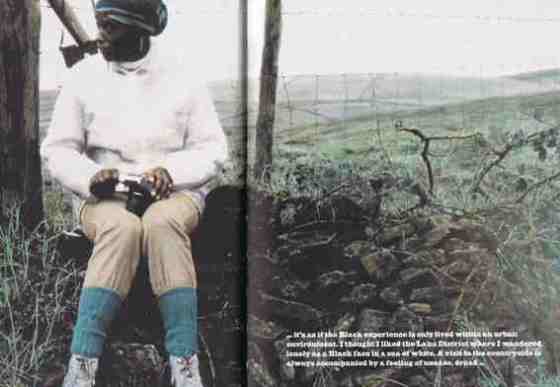

I like to quote other writers on the subject, because they can put it into words better than I can and it also comforts me to know that I am not alone in the way I think about photographs.

‘For me, the best photographs always inspire curiosity rather than satisfy it. I think this ambiguity is one of the most thrilling aspects of the medium. A photograph is only a minute fragment of an experience, but quite a precise and telling fragment’

– Aaron Schuman (in conversation with Alec Soth)

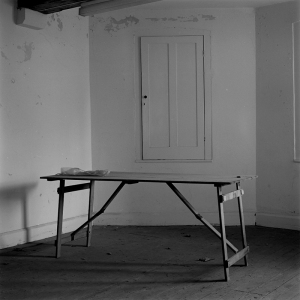

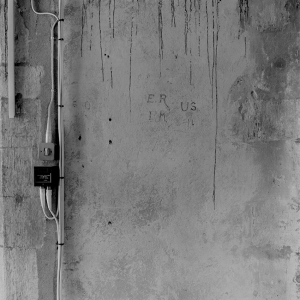

So, here we have two photographs of almost the same area of a room in the upper Salt Tower, both photographs were made on the same visit, but the lower image was a re-shoot of an image I had made on an earlier visit (which could not be used due to a problem with the negative). I re-shot the lower photograph and decided that while I was there I would try a different framing with the complete table in shot.

I can’t remember my exact thoughts when framing up the lower image (I tend to work intuitvely) but I remember liking the line of the cable on the left hand side and the way that it balanced with the line of the rooms corner on the right hand side. I can now see the odd way the corner walls meet at an angle greater than 90 degrees and that this creates a strange perspective. Add to this the way that the table juts into the image offering only a piece of bubble wrap on its dusty surface and the picture begins to feel expectant, it gains a kind of empty wieght; I find this hard to explain but this is something I come to look for in my pictures, what the poet Rilke (when talking about the objects in his Object Poems) described as the ‘silence of their concentrated reality’.

Almost in the center of the image is the tables shadow which seems to drop off, over the edge of the floor, and in the bottom left we have some leaves lying at the run off point of the line of the floor. The small triangle created by the cable on the wall in the top left of the picture is mirrored by the triangle of the table legs in the lower right. This may seem like a strange framing but the more I look at it the more I like its illusion of awkwardness which hides a certain balance. Compare it to the image where the table is in full view: this image lacks any mystery, or oddness and it also lacks balance.